THE HISTORY

FOREIGN VISITORS

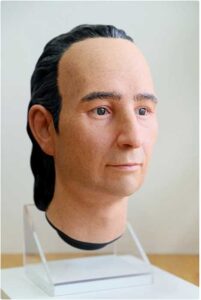

GIOVANNI BATISTA SIDOTTI

Italian missionaries who came to Japan to evangelize Christianity

A second surprise foreign visitor to Yakushima was Giovanni Batsita Sidotti in 1708. The surprise being that foreign visitors were forbidden unless they had permission to arrive to nominated ports – Nagasaki being the most famous. To make matters worse, Sidotti was on a Christian mission to Japan which had outlawed Christianity some 70 years prior to his arrival. Sidotti was arrested upon Yakushima and eventually sent to Edo (current Tokyo) where he formed a strong relationship with his chief interrogator, Arai Hakuseki. The outcome of this relationship were a series of documents written by Hakuseki that offered a glimpse of events taking place in the outside world. Such information was rare during Japan`s two centuries of seclusion known as the Sakoku Period.

Sidotti and Yakushima

Giovanni Batista Sidotti was born in Sicily in 1668. He trained as a missionary in Rome and in 1703 he was sent by the Vatican to Manila with the intention of then finding passage to Japan. While training as a priest, Sidotti had heard stories of missionary martyrdom in Japan and rather than frighten him, these stories appeared to attract him all the more.

The background to this episode begins 150 years earlier when Jesuits commenced their mission based in southern Kyushu. This mission coincides with the latter stages of the Senkoku War and converting to Christianity was often a way of securing shipments of firearms and gunpowder from the Portuguese. During the initial decades, Christianity was accepted into Japan, but once the Senkoku War came to a close around the end of the 16th century then gradually the relationship between the Japanese authorities and the Christians (both foreign and Japanese) began to sour with edicts under Toyotomi Hideyoshi being created to weaken the influence of Christianity among the populace.

After Toyotomi`s death the Tokugawa rulers enforced the edict more ruthlessly by persecuting not only Daimyo that had converted to Christianity, but also commoners, who before then had been largely ignored. Purges began sporadically and Christians were identified, forced into apostasy and monitored afterwards to ensure they weren’t secretly following their religion. There mass executions in which dozens of Christians who refused to renounce their beliefs were executed.

The fight against Christianity played a significant role in the policy of Sakoku (closed country), the national isolation policy that prohibited foreigners from entering Japan and the Japanese nationals from exiting Japan. Trading enclaves were established, most notably in Dejima (Nagasaki) were the foreign contact could be carefully monitored and controlled. Sakoku Policy began in 1633, but was firmly implemented from 1638. The Sakoku Policy continued for two centuries until Commodore Matthew Perry arrived to Yokohama in 1854.

The fight against Christianity played a significant role in the policy of Sakoku (closed country), the national isolation policy that prohibited foreigners from entering Japan and the Japanese nationals from exiting Japan. Trading enclaves were established, most notably in Dejima (Nagasaki) were the foreign contact could be carefully monitored and controlled. Sakoku Policy began in 1633, but was firmly implemented from 1638. The Sakoku Policy continued for two centuries until Commodore Matthew Perry arrived to Yokohama in 1854.

Therefore, in 1708 when Sidotti set sail from Manila to attempt to enter Japan, he was well aware of the consequences should be caught. He received permission for the attempt from Pope Clement XI and found passage on a ship heading towards Japan. He was under the impression that being dressed in kimono and a topknot would be a sufficient disguise to gain entry, but no sooner has his ship taken refuge in a small bay on Yakushima in October 1708 than he was recognized as a gaijin by a local farmer and immediately arrested. The site where Sidotti came ashore can be found in the south of Yakushima in Koshima.

Sidotti was held on Yakushima for a few months before he was transported to Nagasaki to commence his interrogation. The interrogation was led by Arai Hakuseki, a high-ranking advisor to the Shogun Tokugawa Ienobu and his successor Tokugawa Ietsugu. Arai Haruseki was also a great historian and his interest in Sidotti began to develop as the interrogation continued. Hakuseki came to respect Sidotti’s intellect and extensive knowledge of the world and languages. He also appears to have been convinced that according to Sidotti, missionaries were not the advance brigade of a European (Christendom) invasion.

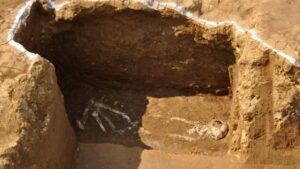

In 1709, Hakuseki was able to gain permission to move Siddoti to Edo (Tokyo) and he was held in the Kirishitan Yashiki (“Mansion of the Christians”), a former school in Edo which had been converted into a prison for suspected crypto-Christians and missionaries in 1646.

Hakuseki recommended to the Shogun that the punishment for Sidotti should be deportation which was far from the usual punishment for his crimes. Hakuseki was unable to convince the authorities to take this measure and Sidotti was further held in a rather relaxed house-arrest. He was given food and other comforts, as well as two attendants (former Christians). Siddoti attempted to re-convert these attendants and his minor mission was discovered causing his demise. He was moved to a dungeon below the Kirishitan Yashiki and died in 1714 – presumably through starvation or illnesses related to starvation.

The fight against Christianity played a significant role in the policy of Sakoku (closed country), the national isolation policy that prohibited foreigners from entering Japan and the Japanese nationals from exiting Japan. Trading enclaves were established, most notably in Dejima (Nagasaki) were the foreign contact could be carefully monitored and controlled. Sakoku Policy began in 1633, but was firmly implemented from 1638. The Sakoku Policy continued for two centuries until Commodore Matthew Perry arrived to Yokohama in 1854.

The fight against Christianity played a significant role in the policy of Sakoku (closed country), the national isolation policy that prohibited foreigners from entering Japan and the Japanese nationals from exiting Japan. Trading enclaves were established, most notably in Dejima (Nagasaki) were the foreign contact could be carefully monitored and controlled. Sakoku Policy began in 1633, but was firmly implemented from 1638. The Sakoku Policy continued for two centuries until Commodore Matthew Perry arrived to Yokohama in 1854.

Therefore, in 1708 when Sidotti set sail from Manila to attempt to enter Japan, he was well aware of the consequences should be caught. He received permission for the attempt from Pope Clement XI and found passage on a ship heading towards Japan. He was under the impression that being dressed in kimono and a topknot would be a sufficient disguise to gain entry, but no sooner has his ship taken refuge in a small bay on Yakushima in October 1708 than he was recognized as a gaijin by a local farmer and immediately arrested. The site where Sidotti came ashore can be found in the south of Yakushima in Koshima.

Sidotti was held on Yakushima for a few months before he was transported to Nagasaki to commence his interrogation. The interrogation was led by Arai Hakuseki, a high-ranking advisor to the Shogun Tokugawa Ienobu and his successor Tokugawa Ietsugu. Arai Haruseki was also a great historian and his interest in Sidotti began to develop as the interrogation continued. Hakuseki came to respect Sidotti’s intellect and extensive knowledge of the world and languages. He also appears to have been convinced that according to Sidotti, missionaries were not the advance brigade of a European (Christendom) invasion.

In 1709, Hakuseki was able to gain permission to move Siddoti to Edo (Tokyo) and he was held in the Kirishitan Yashiki (“Mansion of the Christians”), a former school in Edo which had been converted into a prison for suspected crypto-Christians and missionaries in 1646.

Hakuseki recommended to the Shogun that the punishment for Sidotti should be deportation which was far from the usual punishment for his crimes. Hakuseki was unable to convince the authorities to take this measure and Sidotti was further held in a rather relaxed house-arrest. He was given food and other comforts, as well as two attendants (former Christians). Siddoti attempted to re-convert these attendants and his minor mission was discovered causing his demise. He was moved to a dungeon below the Kirishitan Yashiki and died in 1714 – presumably through starvation or illnesses related to starvation.